What does the past mean to people today?

Our beliefs about the past help define who we are and how we live in the present. Dr Sarah Kurnick, assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder, in the US, studies how ancient Maya peoples at Punta Laguna, Mexico, perceived their own history. The Maya who live in Punta Laguna today play a key role in this research, discovering, interpreting and communicating their own heritage

TALK LIKE AN ARCHAEOLOGIST

ANCIENT MAYA – The ancient Maya flourished in Mesoamerica (contemporary Belize, Guatemala, and parts of Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador) between about 1800 BCE and 1500 CE. The descendants of the ancient Maya continue to live in this region and to speak Mayan languages

CLASSIC PERIOD – The period from about 250 to 925 CE when divine kingship was at its height. This is when we most commonly see the erection of stelae (stone slabs) with detailed hieroglyphic inscriptions, and when we see the peak of famous sites like Tikal

POSTCLASSIC PERIOD – The period from about 925 to 1500 CE when many of the Classic period dynasties ended, leading to more decentralised political structures and less inequality

CIST – a burial chamber

POLITY – a political entity

Archaeology is the study of the human past through material remains. Digging for ancient artefacts may seem innocuous, but archaeology has been political from its beginnings. In some instances, nations have claimed roots in early complex polities like Rome to legitimise contemporary political goals, especially imperialist expansion. In other instances, archaeologists have excavated the graves of indigenous peoples without consideration for the wishes of their descendants or have taken home their finds without obtaining permission from, or compensating, local people. Too often, archaeologists have used data collected about past peoples to benefit themselves and archaeology, and not descendent communities.

To combat this history of injustice, many modern archaeologists, like Dr Sarah Kurnick at the University of Colorado Boulder, practise community archaeology, where archaeological research is done with, by and for local people.

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY

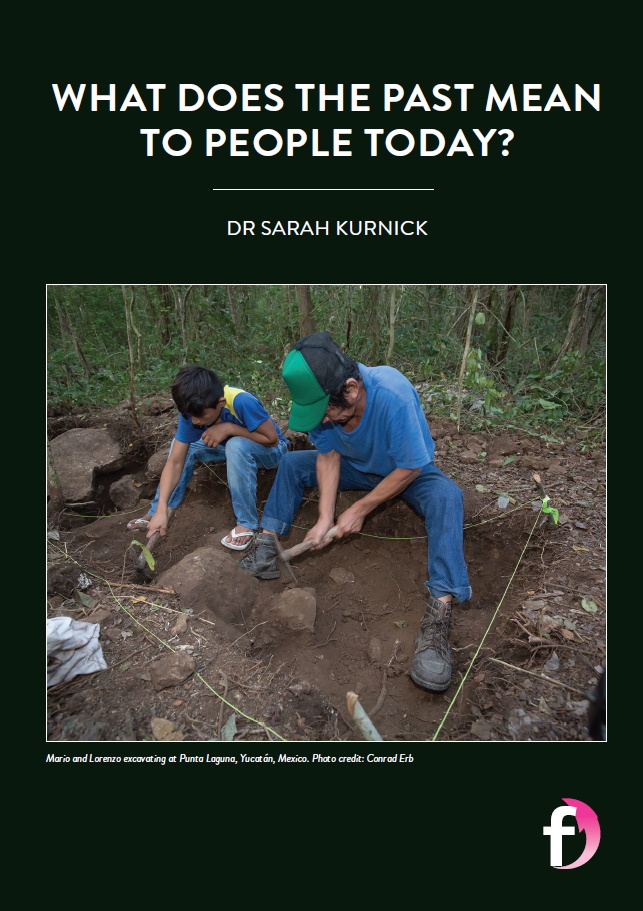

Located in the jungle of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, Punta Laguna is a small Maya village and spider monkey reserve. The Maya who live there today are descendants of the ancient Maya who lived in the same region over a thousand years ago. Sarah and her colleague, David Rogoff of the University of Pennsylvania, are co-directors of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project, a community-led excavation that aims to learn more about the people who once lived in Punta Laguna. This project is an example of community archaeology, where the members of the modern Maya community of Punta Laguna make decisions about research questions, excavations, interpretation of evidence and presentation of findings. The goal is for Maya peoples to take charge of their own history and lead the research into their own ancestors.

Today, Punta Laguna is a tourist attraction, where visitors can explore the archaeological site to learn about the ancient Maya, go on a tour of the spider monkey reserve, canoe across the lagoon and experience contemporary Maya culture. These activities are all run by and benefit members of the local community. One of Sarah’s goals is to help tour guides give visitors comprehensive information about the site’s archaeology. In this way, community archaeology helps participants control narratives about their past while also providing economic benefits for the village.

Not only is community archaeology a moral and ethical imperative but incorporating different viewpoints into the research agenda also makes for better science. Local people will have practical and cultural knowledge of archaeological sites that help them frame important research questions and propose new interpretations. “This project could not exist without the expertise of local community members,” Sarah explains. “They advise us on everything from the nature of political authority among contemporary Maya peoples, to which snakes are poisonous.”

THE ANCIENT MAYA OF PUNTA LAGUNA

Like nearby Cobá, one of the largest ancient Maya cities ever built, Punta Laguna was occupied continuously during the Late Classic and Postclassic periods. Nevertheless, both sites experienced a profound reduction in size and population during the Classic to Postclassic transition. Sarah is studying how the Postclassic Maya perceived their own past. Did they look back on the Classic period as a golden era, or did they distance themselves from their history? Did Postclassic inhabitants at Punta Laguna venerate, destroy or ignore the buildings, monuments and objects constructed by their Classic period ancestors?

So far, members of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project have documented over 200 structures at the site. “Some of these are just above ground level, while the tallest reach over 6m in height,” says Sarah. Many of the structures are solid platforms built of stone that would have supported buildings made from perishable materials, like wood. They may have been houses, religious buildings or administrative centres. Miniature masonry shrines are also common. These one-room stone buildings are too small to enter and may have been the locations of deity or ancestor veneration. Similar shrines have been found at Cobá and at several Maya sites on the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula.

The team’s excavations have also uncovered numerous artefacts, the most common being pieces of ceramic vessels. Obsidian blades, most likely imported from present-day Guatemala, and marine shells, imported from the coast, indicate ancient trade links with Punta Laguna. “Most surprisingly,” Sarah says, “we have excavated an empty cist with two complete vessels, pieces of pyrite and greenstone, and a burial with the remains of two individuals.”

The team’s research so far suggests that the Postclassic occupants of Punta Laguna revered their Classic past. “In one instance, Postclassic people seem to have built a small mound to ceremonially bury two ceramic vessels made during the Classic period,” says Sarah. “We are still working to understand what the site of Punta Laguna reveals more broadly about Postclassic Maya political authority, following the major social transformations that accompany the transition to the Postclassic period.” Sarah and the team will need at least one more field season before they can make more interpretations.

MANIPULATING THE PAST TO CONTROL THE PRESENT

Controlling the image of the past has been a political tool in ancient cultures and is still witnessed today. Consequently, defacing monuments of past public figures is a tradition stretching back thousands of years.

The ancient Akkadians of Mesopotamia defaced a bronze likeness of the historical King Sargon of Akkad. The Mesoamerican Olmec disfigured colossal basalt portrait heads of past rulers. The ancient Romans even had a formal process called damnatio memoriae, where all images of a condemned individual were destroyed. And today, activists in the US pull down and deface monuments of Confederate leaders and other controversial figures such as Christopher Columbus, to protest continuing systemic racism. People of all cultures are concerned with how to present the past, what should be remembered, and how.

The presentation of the past is sensitive because beliefs about a community’s origins and history justify political choices made today. A ruler may use images of successful conquerors of the past to legitimise their own military campaigns. Claims that indigenous peoples lack a sense of national identity or are simply extinct rationalise denial of their sovereignty and their exclusion from political power.

Sarah’s project explores the manipulation of the past at Punta Laguna, for both its Postclassic and contemporary residents. What was the relationship between the Postclassic people of Punta Laguna and their Classic heritage? How did they perceive the decline of the nearby city of Cobá? How will giving control of today’s archaeological research to the modern inhabitants of Punta Laguna help them shape their present? Like their Postclassic ancestors, the modern people of Punta Laguna must have the freedom and power to investigate, interpret and communicate their history to others. Archaeology can aid them in doing so.

DR SARAH KURNICK

DR SARAH KURNICK

Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Colorado Boulder, US

FIELD OF RESEARCH

Anthropological archaeology

RESEARCH PROJECT

How did Postclassic Maya communities at Punta Laguna interact with their Classic Maya past?

FUNDER

National Science Foundation (NSF)

ABOUT ARCHAEOLOGY

Archaeology, which in the US is a subfield of anthropology, is the study of the human past through material remains. While historians read ancient texts to understand the past, archaeologists examine the structures and objects our ancestors left behind.

‘Material culture’ refers to human-made artefacts (e.g., pottery and clothing), art and even the rubbish dumped by ancient societies, as well as human-driven environmental changes such as irrigation and domestication of animals. It also includes the social behaviours associated with these objects and practices. Archaeologists find, catalogue and interpret material culture with the aim of understanding what life was like for past societies.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM229

ANCIENT MAYA – The ancient Maya flourished in Mesoamerica (contemporary Belize, Guatemala, and parts of Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador) between about 1800 BCE and 1500 CE. The descendants of the ancient Maya continue to live in this region and to speak Mayan languages

CLASSIC PERIOD – The period from about 250 to 925 CE when divine kingship was at its height. This is when we most commonly see the erection of stelae (stone slabs) with detailed hieroglyphic inscriptions, and when we see the peak of famous sites like Tikal

POSTCLASSIC PERIOD – The period from about 925 to 1500 CE when many of the Classic period dynasties ended, leading to more decentralised political structures and less inequality

CIST – a burial chamber

POLITY – a political entity

Archaeology is the study of the human past through material remains. Digging for ancient artefacts may seem innocuous, but archaeology has been political from its beginnings. In some instances, nations have claimed roots in early complex polities like Rome to legitimise contemporary political goals, especially imperialist expansion. In other instances, archaeologists have excavated the graves of indigenous peoples without consideration for the wishes of their descendants or have taken home their finds without obtaining permission from, or compensating, local people. Too often, archaeologists have used data collected about past peoples to benefit themselves and archaeology, and not descendent communities.

To combat this history of injustice, many modern archaeologists, like Dr Sarah Kurnick at the University of Colorado Boulder, practise community archaeology, where archaeological research is done with, by and for local people.

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY

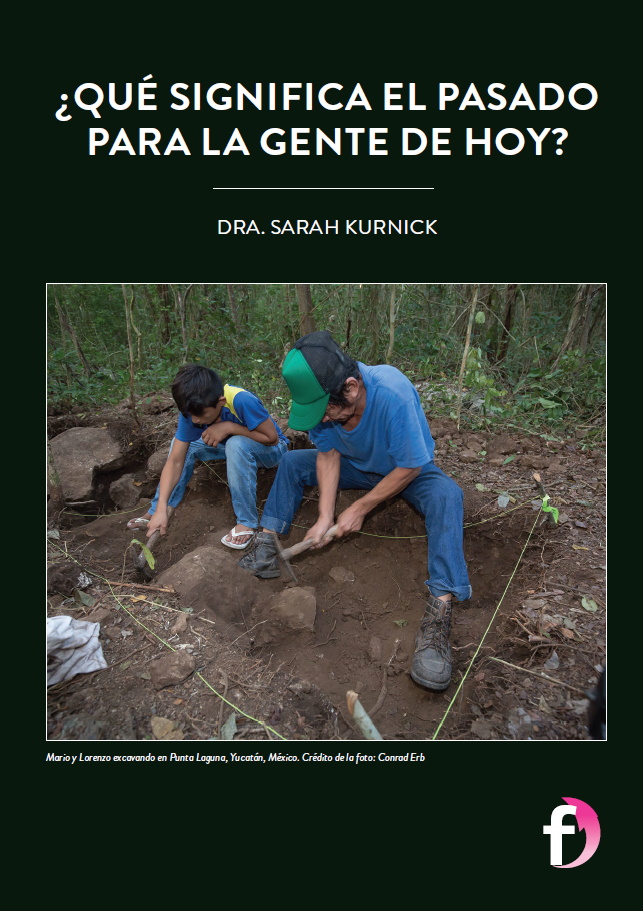

Located in the jungle of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, Punta Laguna is a small Maya village and spider monkey reserve. The Maya who live there today are descendants of the ancient Maya who lived in the same region over a thousand years ago. Sarah and her colleague, David Rogoff of the University of Pennsylvania, are co-directors of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project, a community-led excavation that aims to learn more about the people who once lived in Punta Laguna. This project is an example of community archaeology, where the members of the modern Maya community of Punta Laguna make decisions about research questions, excavations, interpretation of evidence and presentation of findings. The goal is for Maya peoples to take charge of their own history and lead the research into their own ancestors.

Today, Punta Laguna is a tourist attraction, where visitors can explore the archaeological site to learn about the ancient Maya, go on a tour of the spider monkey reserve, canoe across the lagoon and experience contemporary Maya culture. These activities are all run by and benefit members of the local community. One of Sarah’s goals is to help tour guides give visitors comprehensive information about the site’s archaeology. In this way, community archaeology helps participants control narratives about their past while also providing economic benefits for the village.

Not only is community archaeology a moral and ethical imperative but incorporating different viewpoints into the research agenda also makes for better science. Local people will have practical and cultural knowledge of archaeological sites that help them frame important research questions and propose new interpretations. “This project could not exist without the expertise of local community members,” Sarah explains. “They advise us on everything from the nature of political authority among contemporary Maya peoples, to which snakes are poisonous.”

THE ANCIENT MAYA OF PUNTA LAGUNA

Like nearby Cobá, one of the largest ancient Maya cities ever built, Punta Laguna was occupied continuously during the Late Classic and Postclassic periods. Nevertheless, both sites experienced a profound reduction in size and population during the Classic to Postclassic transition. Sarah is studying how the Postclassic Maya perceived their own past. Did they look back on the Classic period as a golden era, or did they distance themselves from their history? Did Postclassic inhabitants at Punta Laguna venerate, destroy or ignore the buildings, monuments and objects constructed by their Classic period ancestors?

So far, members of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project have documented over 200 structures at the site. “Some of these are just above ground level, while the tallest reach over 6m in height,” says Sarah. Many of the structures are solid platforms built of stone that would have supported buildings made from perishable materials, like wood. They may have been houses, religious buildings or administrative centres. Miniature masonry shrines are also common. These one-room stone buildings are too small to enter and may have been the locations of deity or ancestor veneration. Similar shrines have been found at Cobá and at several Maya sites on the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula.

The team’s excavations have also uncovered numerous artefacts, the most common being pieces of ceramic vessels. Obsidian blades, most likely imported from present-day Guatemala, and marine shells, imported from the coast, indicate ancient trade links with Punta Laguna. “Most surprisingly,” Sarah says, “we have excavated an empty cist with two complete vessels, pieces of pyrite and greenstone, and a burial with the remains of two individuals.”

The team’s research so far suggests that the Postclassic occupants of Punta Laguna revered their Classic past. “In one instance, Postclassic people seem to have built a small mound to ceremonially bury two ceramic vessels made during the Classic period,” says Sarah. “We are still working to understand what the site of Punta Laguna reveals more broadly about Postclassic Maya political authority, following the major social transformations that accompany the transition to the Postclassic period.” Sarah and the team will need at least one more field season before they can make more interpretations.

MANIPULATING THE PAST TO CONTROL THE PRESENT

Controlling the image of the past has been a political tool in ancient cultures and is still witnessed today. Consequently, defacing monuments of past public figures is a tradition stretching back thousands of years.

The ancient Akkadians of Mesopotamia defaced a bronze likeness of the historical King Sargon of Akkad. The Mesoamerican Olmec disfigured colossal basalt portrait heads of past rulers. The ancient Romans even had a formal process called damnatio memoriae, where all images of a condemned individual were destroyed. And today, activists in the US pull down and deface monuments of Confederate leaders and other controversial figures such as Christopher Columbus, to protest continuing systemic racism. People of all cultures are concerned with how to present the past, what should be remembered, and how.

The presentation of the past is sensitive because beliefs about a community’s origins and history justify political choices made today. A ruler may use images of successful conquerors of the past to legitimise their own military campaigns. Claims that indigenous peoples lack a sense of national identity or are simply extinct rationalise denial of their sovereignty and their exclusion from political power.

Sarah’s project explores the manipulation of the past at Punta Laguna, for both its Postclassic and contemporary residents. What was the relationship between the Postclassic people of Punta Laguna and their Classic heritage? How did they perceive the decline of the nearby city of Cobá? How will giving control of today’s archaeological research to the modern inhabitants of Punta Laguna help them shape their present? Like their Postclassic ancestors, the modern people of Punta Laguna must have the freedom and power to investigate, interpret and communicate their history to others. Archaeology can aid them in doing so.

DR SARAH KURNICK

DR SARAH KURNICK

Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Colorado Boulder, US

FIELD OF RESEARCH

Anthropological archaeology

RESEARCH PROJECT

How did Postclassic Maya communities at Punta Laguna interact with their Classic Maya past?

FUNDER

National Science Foundation (NSF)

Archaeology, which in the US is a subfield of anthropology, is the study of the human past through material remains. While historians read ancient texts to understand the past, archaeologists examine the structures and objects our ancestors left behind.

‘Material culture’ refers to human-made artefacts (e.g., pottery and clothing), art and even the rubbish dumped by ancient societies, as well as human-driven environmental changes such as irrigation and domestication of animals. It also includes the social behaviours associated with these objects and practices. Archaeologists find, catalogue and interpret material culture with the aim of understanding what life was like for past societies.

A DAY ON A DIG

Excavations, or ‘digs’, are a key part of archaeological research, allowing archaeologists to uncover the remains of past societies. Sarah describes a day of work at Punta Laguna: “We wake up early and start working as soon as it is light enough to see. It is hot, and there are a lot of bugs and snakes. Sometimes there are also spider monkeys watching us. To excavate, we start by clearing vegetation from an area with machetes. We then lay out excavation units with string and wooden stakes, usually in 2 m-by-2 m squares. We use trowels to remove the dirt within each square in 10 cm layers. We excavate very slowly and keep detailed records including notes, drawings, photographs and GPS points. All dirt removed from the units is screened through a mesh and all artefacts are taken back to a lab house. There, we wash them, dry them, label them, count them, weigh them, describe them, and photograph them.”

THE POWER OF THE PAST

Community archaeology harnesses the power of storytelling about the past to create a more just present. Powerful groups in society can use claims about the past to legitimise social and economic inequalities. And marginalised groups can reclaim power and upend social hierarchies by building their own narratives. Archaeologists have a moral imperative to work with, not around, local communities when interpreting their history.

Far from being merely a study of dusty artefacts without impact on the present day, archaeology is a tool for social change. “We need to consider who communicates the past – who decides what is included in history books and who is memorialised in monuments,” Sarah says. “Just imagine how our understanding of history might change if it was told by the marginalised rather than the powerful.”

HOW DID SARAH BECOME AN ARCHAEOLOGIST?

HAVE YOU ALWAYS WANTED TO BE AN ARCHAEOLOGIST?

I’ve always been interested in the past. When I went to college, I thought I was going to study history. Then I started taking classes in anthropology and archaeology and realised that archaeology was a better fit for me. I like working with objects instead of texts and appreciate being able to do research outside.

WHY DO YOU FIND THE ANCIENT MAYA SO FASCINATING?

The Maya area was one of a handful of regions in the world where individuals independently developed agriculture as a means of subsistence, established large, sedentary centres, and developed socially complex hierarchical societies. This makes the ancient Maya a fantastic example of arguably the most important change in all of human history: the transformation of small, nomadic, largely egalitarian groups into large, settled, hierarchical societies.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE FIELDWORK MEMORY?

I always love interacting with children at Punta Laguna, especially the young girls, and giving them tours of our lab house and showing them the artefacts we have excavated.

WHAT DO YOU MOST ENJOY ABOUT YOUR WORK AS AN ARCHAEOLOGIST? AND WHAT DO YOU FIND MOST CHALLENGING?

I enjoy fieldwork the most. There is something incredibly compelling about seeing an object no one else has seen for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Fieldwork is also the most challenging part of the job. The logistics, such as getting permission from foreign governments and securing grant money, are often very difficult and time-consuming. But the effort is worth it!

WHAT HAS BEEN THE HIGHLIGHT OF YOUR CAREER SO FAR, AND WHAT ARE YOUR AMBITIONS FOR THE FUTURE?

Being hired as an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder has definitely been a highlight! In the future, I hope to get tenure [a permanent position] and to continue the Punta Laguna Archaeological Project over the long term.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN ARCHAEOLOGY

• Sarah recommends visiting the website of the Archaeological Institute of America if you want to learn more about the field. It contains articles about careers in archaeology, information about what to do if you think you have discovered an archaeological artefact, and archaeology lesson plans for schools. It also features interactive digs, where you can follow excavations taking place around the world.

• The Society for American Archaeology also has a wealth of information about archaeology, including resources for schools and information about careers.

• Archaeologists do not spend all their time excavating ancient sites in exotic locations! They also work in laboratories, analysing the artefacts they uncover to understand what they represent about past societies and cultures. Archaeologists who work in universities also teach students, ensuring the next generation of archaeologists are equipped to conduct high-quality, ethical research.

• Many archaeologists work in ‘cultural resource management’. This subfield includes managing museum collections, developing educational resources about the human past, evaluating construction sites for potential archaeological finds before work begins, and working for government agencies and non-profit organisations that preserve heritage sites.

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO ARCHAEOLOGY

• Sarah recommends taking anthropology courses as soon as you can. If these aren’t available, history courses will be useful, especially those that focus on regions outside Europe.

• In the US, many universities offer degrees in anthropology which will allow you to major in archaeology. In other countries, specialised archaeology degrees may be available. Most practising archaeologists will have a master’s degree or PhD in archaeology or anthropology.

• Archaeology apprenticeships are available in some countries, providing a practical, hands-on route into the profession. For example, Historic England provides a range of heritage-related apprenticeships.

• Having relevant work experience will be a benefit when applying for university or an archaeology job. Look for opportunities to participate in digs as soon as possible and reach out to local archaeological societies and museums to enquire about excavations and internships.

SARAH’S TOP TIPS

01 Develop relationships with archaeologists (in universities, museums, government agencies, etc.) who can mentor and encourage you. I could not have succeeded without the support of several people who believed in and helped me.

02 Look for internships and field opportunities that you can participate in.

Do you have a question for the Sarah?

Write it in the comments box below and Sarah will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)