Blood, sect and fears

Why do people donate blood to strangers? Professor Jacob Copeman, a social anthropologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, has discovered that religion, culture and politics all play their part

TALK LIKE A SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGIST

RELIGIOUS GURU – a teacher or master of spiritual and religious knowledge

DEVOTEE – a strong believer in a religion who follows the teachings of a guru

Professor Jacob Copeman is a social anthropologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. He has been trying to understand why people are motivated to donate their blood, and how this fits into the fabric of our societies. He has discovered that there is far more to donating than medical facts. Giving blood is also about politics, religion and social influencers.

WHAT IS VOLUNTARY BLOOD DONATION?

There are some medical conditions such as anaemia and leukaemia that affect the health of a person’s blood. These can be treated by giving the patient healthy blood from someone else and injecting it into a blood vessel. This process is known as a blood transfusion, and it is also used to help people who have lost blood during surgery, childbirth or an accident. Blood transfusions save millions of lives around the world, but they would be impossible without blood donations.

Voluntary blood donation is where somebody gives their blood to be used by whoever might need it, without getting any payment in return. Alternatively, a donor might give their blood to a central blood bank because they have a relative who needs a blood transfusion. This is known as a replacement donation. A third type of donation is a commercial one, where the donor receives a payment. However, voluntary donation is considered the safest method for patients, and is strongly encouraged by the World Health Organization (WHO).

WHAT HAS BLOOD DONATION GOT TO DO WITH ANTHROPOLOGY?

In your biology classes you will have learned that blood is a bodily fluid made up of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. But is this the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word blood? Depending on your beliefs and culture, you might associate blood with family connections, Christ on the cross, halal meat, war, sacrifice, or any number of other things. Blood donation, therefore, means different things to different people, and this is what anthropologists such as Jacob are interested in.

Jacob has covered attitudes towards blood donation around the world, in countries that include Brazil, China, India, the Navajo Nation, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka and the United States. He says it is an “extraordinary emotive force for some communities, and often the source of controversies”. Jacob has looked at how non-governmental organisations (NGOs) teach the science of blood regeneration to help allay people’s fears about donating, how blood banks work, how people link blood donation to ancient Indian ideas of gift-giving, how blood is used in political activism, the use of human blood in art, and the relationship between blood donation and time (encapsulated in the motivational slogan: ‘Donate blood. It means only a few minutes to you…but a lifetime for somebody else’). Here we will concentrate on the part of his work investigating what motivates people to give blood in India.

HOW DID BLOOD DONATION BECOME A RELIGIOUS PRACTICE IN INDIA?

In all cultures, there are some people who are particularly respected, and can influence the decisions of other people. For example, in the UK these people include celebrities, sportspeople or social media influencers. In India, some of the most influential people are Hindu and Sikh gurus, and it was thanks to them that voluntary blood donation became popular in the 1980s.

Before the gurus became involved, many people in India were sceptical about giving blood. They had their own cultural understanding of medicine and blood, and many were suspicious of new western medicine. Many believed that giving blood would lead to permanent weakness (in fact, your body regenerates completely in 4-8 weeks). As a result, few people came forward.

Doctors realised that gurus had the power to change the attitudes of their devotees. If a guru endorsed blood donation, their devotees then saw it as a way of expressing their religion and showing their respect for the guru. For many devotees, giving blood was transformed from a strange new medical practice into a sacred ritual, and donations sky rocketed. As they did so, questions started to arise about the structure of Indian society itself.

HOW DID BLOOD DONATION CHALLENGE THE INDIAN CASTE SYSTEM?

The Indian caste system is a traditional division of society, in which people in the upper castes are considered superior to those in lower castes. Often, the differences between castes are thought to be biological in nature. Many people might believe that there is something contained in a person’s blood that indicates which caste they belong to.

However, blood donation has shown people that this is not the case. In reality, there are different types of blood (called A, B and O), but people from different castes can have the same blood type. This means that blood donations cross the boundaries of caste, and help Indian people feel more connected as a country. In fact, the idea that donating blood is a way of contributing to the nation has found its way into Indian politics.

WHY DO POLITICAL PARTIES IN INDIA HOLD BLOOD DONATION EVENTS?

Blood donation is seen as patriotic due to India’s history. When people fought to become independent from British colonial rule, they spilt their blood for the sake of their country. India became a free country in 1947, but was later invaded in 1962 by China. During the war, many who were not fighting donated their blood to treat injured soldiers. These memories, in addition to the way blood crosses the caste boundaries, make giving blood a symbol of national pride.

As a result, political campaigns often involve blood donation events. Jacob has observed many such events, and remembers vividly the atmosphere at the first one he attended. “As they donated their blood beneath a colourful marriage tent, activists signed an anti-corruption pledge, joined hands and chanted ‘Long live Sonia Gandhi’, who is leader of the Indian National Congress political party.” Sometimes, political parties even compete to donate the most blood, as a display of political rivalry.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF BLOOD DONATION?

A key message of Jacob’s work is that if we want to change people’s behaviour, then we must first understand their culture. In the case of Indian blood donation, people often were not persuaded by doctors; many, instead, put their trust in religious gurus. In order to encourage people to give blood, the gurus first had to be convinced that it fitted with their beliefs. If this had not happened, Indian blood banks might still be trying, unsuccessfully, to persuade large swathes of the population that donating blood is safe and effective.

One important facet of anthropology is that it helps us to understand what motivates groups of people, and who the influencers are in different societies. You may be a voluntary blood donor one day, if – that is – the blood bank understands who or what motivates you!

PROFESSOR JACOB COPEMAN

PROFESSOR JACOB COPEMAN

Research Professor

University of Santiago de Compostela

Distinguished Investigator, Galician Innovation Agency (GAIN)

Spain

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Social Anthropology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the political and religious elements of voluntary blood donation, particularly in India

FUNDER: The Economic and Social Research Council

ABOUT SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY

How do social structures and practices differ, and how are they the same? What defines culture, and what is universally human? These are the questions that anthropologists try to answer. They do so by studying peoples’ lives in detail, often by living alongside communities for extended periods of time.

DO ANTHROPOLOGISTS STUDY REMOTE TRIBES?

Social anthropology is often associated with the study of small, isolated communities. While this is sometimes the case, anthropologists are interested in much more. Ultimately, any community, from any part of the world, has its own unique features and could be the subject of anthropological research.

WHY IS SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY IMPORTANT IN MEDICINE?

Advances in medicine are useless unless they are accepted by a society. The last time you swallowed a pill, did you stop to check the ingredients and find out how it works? Probably not, because you trust the pharmacy or doctor who gave you the pill. Building that trust between medicine and society is vital, and that is where anthropology can help.

Medical anthropologists explore belief systems, power structures and motivations in different medical contexts. This can help the medical profession to communicate effectively with different populations. Jacob’s work on blood donation in India is just one example of this type of anthropology.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM183

RELIGIOUS GURU – a teacher or master of spiritual and religious knowledge

DEVOTEE – a strong believer in a religion who follows the teachings of a guru

Professor Jacob Copeman is a social anthropologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. He has been trying to understand why people are motivated to donate their blood, and how this fits into the fabric of our societies. He has discovered that there is far more to donating than medical facts. Giving blood is also about politics, religion and social influencers.

WHAT IS VOLUNTARY BLOOD DONATION?

There are some medical conditions such as anaemia and leukaemia that affect the health of a person’s blood. These can be treated by giving the patient healthy blood from someone else and injecting it into a blood vessel. This process is known as a blood transfusion, and it is also used to help people who have lost blood during surgery, childbirth or an accident. Blood transfusions save millions of lives around the world, but they would be impossible without blood donations.

Voluntary blood donation is where somebody gives their blood to be used by whoever might need it, without getting any payment in return. Alternatively, a donor might give their blood to a central blood bank because they have a relative who needs a blood transfusion. This is known as a replacement donation. A third type of donation is a commercial one, where the donor receives a payment. However, voluntary donation is considered the safest method for patients, and is strongly encouraged by the World Health Organization (WHO).

WHAT HAS BLOOD DONATION GOT TO DO WITH ANTHROPOLOGY?

In your biology classes you will have learned that blood is a bodily fluid made up of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. But is this the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word blood? Depending on your beliefs and culture, you might associate blood with family connections, Christ on the cross, halal meat, war, sacrifice, or any number of other things. Blood donation, therefore, means different things to different people, and this is what anthropologists such as Jacob are interested in.

Jacob has covered attitudes towards blood donation around the world, in countries that include Brazil, China, India, the Navajo Nation, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka and the United States. He says it is an “extraordinary emotive force for some communities, and often the source of controversies”. Jacob has looked at how non-governmental organisations (NGOs) teach the science of blood regeneration to help allay people’s fears about donating, how blood banks work, how people link blood donation to ancient Indian ideas of gift-giving, how blood is used in political activism, the use of human blood in art, and the relationship between blood donation and time (encapsulated in the motivational slogan: ‘Donate blood. It means only a few minutes to you…but a lifetime for somebody else’). Here we will concentrate on the part of his work investigating what motivates people to give blood in India.

HOW DID BLOOD DONATION BECOME A RELIGIOUS PRACTICE IN INDIA?

In all cultures, there are some people who are particularly respected, and can influence the decisions of other people. For example, in the UK these people include celebrities, sportspeople or social media influencers. In India, some of the most influential people are Hindu and Sikh gurus, and it was thanks to them that voluntary blood donation became popular in the 1980s.

Before the gurus became involved, many people in India were sceptical about giving blood. They had their own cultural understanding of medicine and blood, and many were suspicious of new western medicine. Many believed that giving blood would lead to permanent weakness (in fact, your body regenerates completely in 4-8 weeks). As a result, few people came forward.

Doctors realised that gurus had the power to change the attitudes of their devotees. If a guru endorsed blood donation, their devotees then saw it as a way of expressing their religion and showing their respect for the guru. For many devotees, giving blood was transformed from a strange new medical practice into a sacred ritual, and donations sky rocketed. As they did so, questions started to arise about the structure of Indian society itself.

HOW DID BLOOD DONATION CHALLENGE THE INDIAN CASTE SYSTEM?

The Indian caste system is a traditional division of society, in which people in the upper castes are considered superior to those in lower castes. Often, the differences between castes are thought to be biological in nature. Many people might believe that there is something contained in a person’s blood that indicates which caste they belong to.

However, blood donation has shown people that this is not the case. In reality, there are different types of blood (called A, B and O), but people from different castes can have the same blood type. This means that blood donations cross the boundaries of caste, and help Indian people feel more connected as a country. In fact, the idea that donating blood is a way of contributing to the nation has found its way into Indian politics.

WHY DO POLITICAL PARTIES IN INDIA HOLD BLOOD DONATION EVENTS?

Blood donation is seen as patriotic due to India’s history. When people fought to become independent from British colonial rule, they spilt their blood for the sake of their country. India became a free country in 1947, but was later invaded in 1962 by China. During the war, many who were not fighting donated their blood to treat injured soldiers. These memories, in addition to the way blood crosses the caste boundaries, make giving blood a symbol of national pride.

As a result, political campaigns often involve blood donation events. Jacob has observed many such events, and remembers vividly the atmosphere at the first one he attended. “As they donated their blood beneath a colourful marriage tent, activists signed an anti-corruption pledge, joined hands and chanted ‘Long live Sonia Gandhi’, who is leader of the Indian National Congress political party.” Sometimes, political parties even compete to donate the most blood, as a display of political rivalry.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF BLOOD DONATION?

A key message of Jacob’s work is that if we want to change people’s behaviour, then we must first understand their culture. In the case of Indian blood donation, people often were not persuaded by doctors; many, instead, put their trust in religious gurus. In order to encourage people to give blood, the gurus first had to be convinced that it fitted with their beliefs. If this had not happened, Indian blood banks might still be trying, unsuccessfully, to persuade large swathes of the population that donating blood is safe and effective.

One important facet of anthropology is that it helps us to understand what motivates groups of people, and who the influencers are in different societies. You may be a voluntary blood donor one day, if – that is – the blood bank understands who or what motivates you!

PROFESSOR JACOB COPEMAN

PROFESSOR JACOB COPEMAN

Research Professor

University of Santiago de Compostela

Distinguished Investigator, Galician Innovation Agency (GAIN)

Spain

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Social Anthropology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the political and religious elements of voluntary blood donation, particularly in India

FUNDER: The Economic and Social Research Council

ABOUT SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY

How do social structures and practices differ, and how are they the same? What defines culture, and what is universally human? These are the questions that anthropologists try to answer. They do so by studying peoples’ lives in detail, often by living alongside communities for extended periods of time.

DO ANTHROPOLOGISTS STUDY REMOTE TRIBES?

Social anthropology is often associated with the study of small, isolated communities. While this is sometimes the case, anthropologists are interested in much more. Ultimately, any community, from any part of the world, has its own unique features and could be the subject of anthropological research.

WHY IS SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY IMPORTANT IN MEDICINE?

Advances in medicine are useless unless they are accepted by a society. The last time you

swallowed a pill, did you stop to check the ingredients and find out how it works? Probably not, because you trust the pharmacy or doctor who gave you the pill. Building that trust between medicine and society is vital, and that is where anthropology can help.

Medical anthropologists explore belief systems, power structures and motivations in different medical contexts. This can help the medical profession to communicate effectively with different populations. Jacob’s work on blood donation in India is just one example of this type of anthropology.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY

• Anthropology is global in its reach, and gives you the tools to research the nature of societies, communities and organisations. Learn more about the subject at

www.discoveranthropology.org.uk.

• The American Anthropology Association has a YouTube playlist showcasing anthropologists in a wide range of specialities: www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL0OchlJ85m4f_2–kdkxQlt9ozy9CQc2K

• You could work in academia, policy, development, social work, business and in many other sectors. Salaries for academic anthropologists in the UK range from £32,000 to £82,000.

• To study anthropology at university, you will need to show an interest in how different societies work, and the people who make up these different societies.

• English literature, religious studies and history will all stand you in good stead as an anthropologist. However, most universities do not require specific subjects.

• Some anthropologists come to the field after studying another arts or humanities subjects. Jacob, for example, studied English for his first degree.

HOW DID JACOB BECOME A SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGIST?

WHAT DID YOU KNOW ABOUT ANTHROPOLOGY WHEN YOU WERE GROWING UP?

Nothing! I first encountered social anthropology when I was at university. Out of interest, I took a course in the anthropology of emotions and personhood. This sparked an interest in both anthropology and India which, having completed my BA in English Literature, led to me taking a conversion Master’s course in social anthropology at the University of Cambridge, and choosing a dissertation project based in India.

HOW DID YOU REALISE ANTHROPOLOGY WAS SOMETHING YOU WANTED TO GET INVOLVED WITH?

I was unaware of anthropology as a subject until I was in my late teens, so I certainly didn’t grow up thinking I’d be an anthropologist – I don’t think many people do! However, in my early teens, I developed keen interests in politics, religion and culture. When I discovered anthropology as a discipline, I realised these interests were an excellent basis for anthropology. In my time, I’ve also wanted to run an independent arts venue, and be a writer on music and sport.

HOW DID YOU COME TO STUDY BLOOD AND BLOOD DONATION?

I came to this topic by doing a PhD on the social aspects of blood donation in India. In particular, it explored the transition from a system of commercial donation to a voluntary donation system. By accident, this became a study of religion and religious change. What I hadn’t realised before I got to Delhi to do the research was that a key strategy of blood banks was to enthuse religious gurus, whose support of voluntary blood donation motivated their devotees to take part. In this way, the study of blood and blood donation lead on to other themes, all of which I continue to research. You just never know where your research will take you.

WHAT QUALITIES DO YOU HAVE THAT MAKE YOU A GOOD ANTHROPOLOGIST?

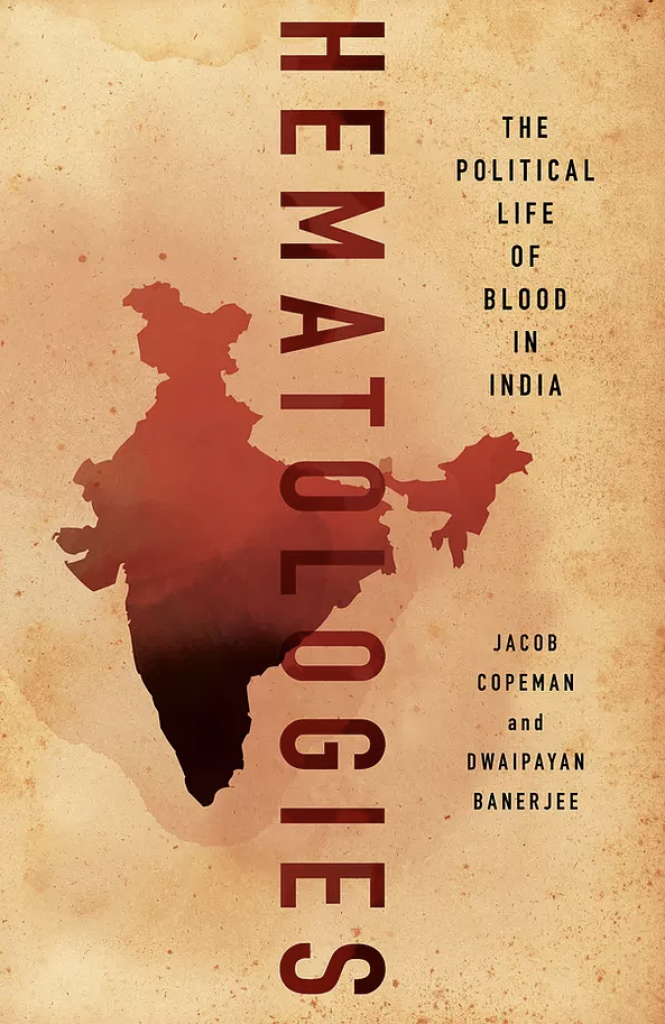

I get excited by ideas – that helps; a love of reading, too; plus an interest in the interconnectedness of disciplines and ideas; and keenness to interact with people. I like – and have been reasonably successful in – collaborating with others: both the people whom I meet while undertaking fieldwork in India, and also other scholars. For one of my books on blood in India (Hematologies: The Political Life of Blood in India) I collaborated with Professor Dwaipayan Banerjee, who is in the science studies programme at MIT in the US. Working with Dwai was stimulating and inspiring. We never actually met during the writing process; everything was done via email.

WHAT DO YOU LOVE ABOUT THE WORK YOU DO?

I have always been curious about how societies work, and the differences and similarities between different societies and cultures. I love the fact that I can follow my curiosities and explore these in such depth. I meet interesting people all over the world, and have the opportunity to be part of events I would otherwise know nothing about, from mass blood donation camps in India to spectacular religious ceremonies.

I also love the global reach of being an academic researcher. Academia is an international community, and I benefit hugely from the cross-fertilisation of ideas that comes from collaborating with academics around the world.

JACOB’S TOP TIPS

01) Develop your curiosity for how different cultures, organisations and societies work. Read newspapers, follow relevant media channels, watch relevant TV programmes. Be curious when travelling, both in the UK and abroad.

02) Only a small number of social anthropologists follow an academic career. Explore other sectors where your degree will be valuable, including education, HR, PR, social work, museum work, charity and international development, policy work, market research, film or business. Gain practical experience during your studies to help you decide which sectors interest you most.

03) Remember that many people will not fully understand what social anthropology is about, and you may need to explain it concisely to future employers. Be ready to talk about the valuable skillset you will develop through your studies.

Do you have a question for Jacob?

Write it in the comments box below and Jacob will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)